“Let’s get Mom a bumper sticker that says, ‘This car stops at all historical sites,” Lynae suggested as they drove south Interstate twenty-five.

“OK, OK. I promise not to stop at any more museums after Mesilla. Look, it says "Historical area," so it has to be good.

“Mom, this is your trip, we'll be fine, go ahead and turn off at Mesilla." Brent encouraged from the back seat reaching around holding his hand over Lynae’s mouth to stop her protests.

“Oh, look, it’s a little plaza, a town square. All the little towns used to have a plaza like in Santa Fé, but this is just so tiny and cute. Let's park and look around, it doesn't look like anything is open, but we can at least read the signs."

"Look, Mom. That store just opened up, and the others are opening. We came just in time. OOO Kaay, Shopping!!" Lynae’s countenance suddenly changed.

”Well Lynae is happy now. She can spend money," was Brent’s uninvited interpretation.

"O como me moletsas tu, hijito mío. Leave her alone. It's her money. She earned it baby sitting." Mom hushed her youngest son’s criticism.

“Oh, look at the candles. I love them.” Lynae chirped.

“Yeah, look at the prices.” Mom scowled.

"Here, Brent, you need this hat!" Lynae said shoving a tall imitation beaver hat onto her brother’s head.

"Yeah, right, like I need an extra thumb," Brent harrumphed secretly admiring his reflection in the mirror behind the counter.

"So, what can be seen in Mesilla?" Mom asked the store clerk. Lynae hid around the corner suddenly embarrassed, making an effort to look as if she were shopping alone.

“Well, right over there,” the lady gestured, is the monument where the Gadsden Purchase was signed. Across the street is Kit Carson's hide out --"

"OK, what's the Gadsden whatever, and who is Kit Carson?" Lynae asked coming in to the last part of the conversation, curiosity apparently over powering her embarrassment.

"You really should watch more TV, kiddo.” Mom joked. Everything I know about history I learned from TV movies. Kit Carson was an out law, but I think he had some heroic episode in the Civil war; and the Gadsden Purchase was when the United States bought some land somewhere around here, and -- I guess I don't know much about history, after all. But I remember hearing that he killed one of our ancestors. I don’t remember details.

“Let's read the sign. Wait, I'll go back to the car and get the camera. You kids go on ahead. Take the lunch basket and the blanket -- I'll be right there."

"Race you to the historical marker." Brent jabbed Lynae and began running, still decked out in the beaver hat. They reached the marker together; huffing and puffing they threw themselves down on the grass as if they had run a marathon.

Looking for the marker, they saw instead a platform and people standing or sitting on blankets all around. A speaker began a historical review. He removed his tall hat and gestured grandly. Lynae began to recognize the sudden changes as she tried to tune into a string of seemingly unconnected phrases:

"Since the war we waged with the United States as Mexican citizens . . . we won the battle at the Alamo. . .”

“I saw that movie, John Wayne and everyone else died in the end.” Brent said beginning to pay attention to the speaker, as he settled onto the grass.

“Even though we lost in the final attempts to keep that territory of Texas . . . we used what we learned to declare independence from Spain. . . . American frontiersmen moved into Texas before it became independent from Spain. They pledged to become Mexican citizens and accept the Catholic religion for their own.”

Lynae poked at Brent, “That’s what Becknell was telling us.” Both sat up and began to listen as they scanned the crowd for familiar looking faces while the speaker droned on.

"With Mexico declaring independence, Texas became a part of Mexico. The new comers backed out on many of their promises ... Mexico was attempting to abolish slavery, a threat to the Texans economic security.... The United States tried to buy the area from Mexico. They wanted to make Texas a separate republic from Mexico.”

Lynae spotted two young families sitting near them on the grassy slope. Antonio María García and María Josefa Martinez with their young children including, José Rafael García. And close by on a blanket was Antonio’s sister, María Inez Faviana García with her very handsome husband, Nazario Baca. They had just been married a few years.

A new speaker continued the story in a more animated rendition of New Mexico history:

"President Santa Ana began in l836 to stop the uprising of the Texicans. ‘Remember the Alamo,’ became the war cry of the Texan. Sam Houston and Andrew Jackson caught Santa Ana in a bad position on the San Jacinto River and forced the Mexican army to flee. Santa Ana was captured by the Texas soldiers and forced to declare independence from Mexico for Texas.”

“So are we Mexicans, Texicans or Americans now?" Lynae whispered to Brent, who appeared to be spell bound by the orator.

"Just shut up and listen,” was all he responded -- then admitted, shaking his head solemnly, "I'm not really sure.”

“By 1845 President James Polk had taken office. He sent an envoy to Mexico to buy California and New Mexico and some land along the Río Grande that was still disputed between Mexico and Texas. Mexico refused to receive the envoy. Not until April 25, 1846, Mexican soldiers came across the Río Grande and engaged an American force.

“The President immediately asked Congress to declare war on the grounds that U.S. territory had been invaded, a point not very convincing since Mexico had at least as good a claim to it as the U.S. did. In fact, it could well be argued that U.S. had been guilty of aggression when Taylor's men moved into the Río Grande area,” the speaker interpreted.

"That was that Pike episode. Lynae, remember Pike?" Brent started punching at Lynae’s arm as he became more animated, finally catching on to the newest scene in history.

"But U.S. Congress agreed with Polk and declared war against Mexico. General Taylor engaged Santa Ana in Northern Mexico. Vera Cruz was taken in March l847, then the soldiers marched into Mexico City in September.”

Lynae began to loose interest in the speaker and look around for babies. "Oh, look at the cute baby," she cooed, not so much to Brent as to the baby.

Brent mimicked, "OOOO loook at the cuuuute Baaab-eee.”

“Brent, you’re such a BOY! “ Lynae applied her favorite insult to her brother.

"What's your baby's name?” Lynae asked the distracted mother of two little children sitting near by.

“This is María Eugenia,” Dolores Aragón answered softly, playing with the baby’s tiny fingers.”

“She is the daughter of Rafael Garcia y Martinez, and you must be Dolores Aragon! “

Dolores cooed gently rocking the young toddler, acknowledging that she was indeed the great-grandmother Lynae had identified, while at the same time grasping the restless five year old Antonio at her side. “O, como me molestes tu, hijito.” She said warmly but firmly.

"You've got your hands full," Lynae said, modeling the concerned motherly-voice she had heard from both Mom and Gina. I can help you hold one of them ‘til the program is over."

Lynae took baby María Eugenia into her lap and played with her quietly through the rest of the history lesson.

"Meanwhile, Santa Fé and New Mexico had been taken without a struggle." The speaker was saying. "Kit Carson got word to the U.S. soldiers that California had already staged a successful revolt."

"Now who was Kit Carson, again?" Lynae questioned Brent, who shrugged her off with a wave of his hand, pointing in the direction of what had just been a curio store across the street.

Lynae focused on the building. Now it was not a store, but a house. It was obviously, just as the sign had said, the home and hide out of the notorious Kit Carson.

Christopher Houston "Kit" Carson

Kit Carson MuseumTaos, NM

"John C. Fremont led the Americans and raised a U.S. flag over the territory with the assistance of some American ships which had been lying off shore for just such a break."

"Is he going to go on all day about this?" Lynae spoke in her best 'motherese' to the little girl cradled in her lap. "Do you know that you are really my great-grandmother?" she added in the same tone of voice.

Noticing there had been a change of speakers, Lynae glanced at the stage. The subject, of course, was still the same -- history of New Mexico.

"In l848, five years ago, the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo was written on U.S. terms. The United States received clear title to Texas and got all of New Mexico and California for a purchase price of fifteen million dollars and any claims of American citizens against Mexico. From this New Mexico and California territories, as well as the territories of Nevada, Utah, Arizona, Colorado and New Mexico have been mapped out."

"So I guess we are part of the United States now! All of the southwestern states have been purchased!" Brent explained to Lynae, who he realized was not really listening, but playing with their baby great-great-grandmother.

"The U.S. decided to add more land to this territory, as a route for a new railroad to Southern California. James Gadsden was set to buy the land for ten million dollars and establish a new southwestern boundary to the United States of America.”

“So it is on this occasion, that we sign the purchase papers, and by doing so, all the families of the New Mexico and Arizona territories become citizens of the United States of America!"

The crowd broke into cheers and applause, although there were some who seemed to be attending more in protest of the political move than in support of it. Lynae grasped the food basket Dolores had indicated following her to an open area where they spread out their picnic lunches and prepared to eat. Mom wasn't back yet, and there was no sign of the cars that had been parked near the plaza just a few minutes before.

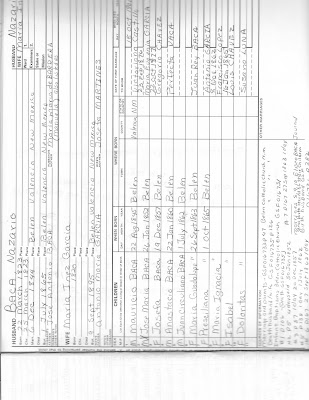

"Lynae, Brent, these are our good friends from Belén, Nazario Baca and María Inez Faviana García. Their two sons, Mauricio and José María.”

"Otro abuelito!" Lynae gasped in excitement, but quickly changed it to more of an "oomph" sound as Brent elbowed her in the ribs.

“Good save,” he teased.

"I mean, mucho gusto conocerles, ustedes.” She chanted one of the few Spanish phrases she had learned from Brent, even though she knew her English was automatically translated into Spanish.

“Your little boys are just darlings." Turning to Brent, she repeated, “That's our Great Grandfather Nazario and his Papá Baca!" Brent was just as excited. Here was José María Baca, the notorious grandfather Uncle Eliseo had described to them -- a little boy not quite three years old. And here they were, having a picnic with him to celebrate the Gadsden Purchase making New Mexico a part of the United States. No wonder he was so involved in New Mexico becoming a state -- he would later insist that all his sons go to school in Kansas City to learn perfect English to prepare for becoming a state.”

"WOW -- I mean-wow." Brent stammered.

"Yes, we are all excited about the new changes in government.” The older Baca acknowledged, interpreting Brent’s enthusiasm to be about the announcement. “After being independent from Spain and a part of Mexico, now we change again to become a territory of the United States of America. One day, maybe, New Mexico and Arizona will be states." Brent just nodded, wanting to tell him how correct his guess was.

Somehow the historical nature of the speakers now became so much more interesting to both Lynae and Brent. The excitement of being with their great-great-great grandparents, and their children, the great-great-grandparents seemed to put the purchase more into perspective.

"You know how Mom and Uncle Duane tease Grandma Lucy when she says, "We are not Mexican we are Spanish." Brent folded his hands in his lap in an impression of Uncle Duane’s imitation Grandma Lucy. We would have been Mexican if the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and the Gadsden Purchase hadn't been signed. We would be a state of Mexico instead of one the United States. You’d be singing Fifty-Nifty Mexican States instead of Fifty Nifty United States.©

[1]"Well, if Mexico hadn't declared independence before that, we would be Spanish -- so Grandma is partially right. I guess it was just a matter of when and where they drew the lines on the map.”

After lunch and a long restful siesta, the families gathered again to continue the celebration. During the afternoon Lynae and Brent learned more about the astounding changes in politics and government over that first quarter of the nineteenth century that had meant so many differences in the lives they were living at the end the twentieth.

“During the time of the Civil War, Napoleon III of France wanted to follow in the footsteps of his famous ancestor, looking for land to include in an overseas empire. He thought he saw his chance in Mexico which owed money to several European nations, which were having trouble collecting. To force payment, England, France and Spain sent troops to occupy Mexico. The financial matter was promptly settled and England and Spain withdrew.

France stayed on; Archduke Maximilian of Austria was placed in command as France's Emperor of Mexico. When the war was over we immediately demanded that France get out, and sent troops to the Río Grande to back up our demands. And France got out leaving Maximilian to his fate at the hands of the Mexicans. Napoleon III finally withdrew from Mexico because of his threatened position in France, avoiding a serious showdown and testing the strength of American foreign policy as it had been established by the Monroe Doctrine.”

All during the evening festivities, the Bacas and the Aragóns introduced Brent and Lynae to more family visiting from Belen: Manuel Antonio, and Adoina de la Trinidad, José Aragón and Manuela Antonia Torres: parents of María Dolores de los Reyes; Policárpio Bustamante and Guadalupe Larranaga, along with their young son, José Antonio, born 1847 in Lemitar, Socorro county and some of their eight children born in Lemitar and Rody.

Gregario Chávez was another young child, born 1850. He had come with his parents Juan Chávez and Monica Vaca.

The mariachi band blared as children slept on blankets on the grass as their parents and older siblings danced and sang in celebration through the starry summer night. Brent and Lynae spread their blanket and joined in a game of cards. The deck was an Apache adaptation of ancient Spanish playing cards. Each deck had forty cards decorated with swords, cups, coins and clubs. Inspecting the decks, Brent soon realized there were no eights, nines or tens; neither was there a queen. The face cards consisted instead of a king and a page and a caballero or knight, decked out in fancy costumes of the Apache rather than the typical court dress in Madrid.

They both quickly learned to play the popular game of Monte, betting against the dealer. The family members bet with small sticks or piñon nuts and did not gamble money, but many a man had lost all his money to card games in the plazas of New Mexico towns.

The early morning silence was split by the sounds of cannon shots and buglers greeting the dawn. Brent stood proudly with his bugle blasting away along with last night’s mariachi musicians, awaking the exhausted partiers.

Rafael Torres, leaping from his blanket at the foot of his wagon grabbed Brent’s horn and threatened that if he blew one more note he would shove the whole thing down his throat.

Lynae joined with Rafael in berating Brent. “Just because you earned your Boy Scout merit badge with your bugle, doesn’t give you the right to wake up the entire world.”

Rafael’s wife, Rafaila Baca and older daughter, Manuela Antonia Agapita calmed Rafael, coming to Brent’s defense. “That’s no way to treat the boy,” José Aragon, Manuela’s husband agreed. We are all one country now, and one family. Let us be loving and kind.

After a huge community breakfast cooked in Dutch ovens and on open fire grills, the celebration continued. Brent remarked that it reminded him of some of the family reunions in their own decade.

Once again the families spread their blankets on the grass facing the speaker's platform. The United States Stars and Stripes fluttered gracefully above the stand in the cool morning breeze as more speakers stood to relate the history of this new and ever important Gadsden Purchase of l853.

“After Pike had shown the way, several Americans attempted both to trade with the isolated province of New Mexico and to trap in its streams between 1807 and 1821. In general these efforts were futile, as the Spanish continued to take the necessary safeguards against an influx of Americans.

“In the year 1821 a combination of circumstances led to a changed atmosphere. First of all, the success of the revolt in Mexico meant that Spain's authority was ended. And Mexican officials were to prove far less competent in halting the inroads of Anglo-Americans than Spain, perhaps because the government at Mexico City was unable even to give the little support extended when the Spaniards were in control.”

Lynae poked at Brent’s contraband beaver hat, which he had quite unintentionally shoplifted the previous day, one hundred sixty some years in the future. The speaker summarized the immigration of adventurers that swept into the South West after Pikes reports were made public, and their attempts to establish trade with New Mexico.

“They were men of all races, types and cultural background, bound together by one thing: fascination with the wild, free and irresponsible life of the trapper. Some were well educated, while others were illiterate frontiersmen, typical of those who had steadily pushed the reigns of civilization westward from the Atlantic seaboard. Through the books, letters, and even oral reports carried by these men, the rest of the United States was to learn rapidly about the west. Once fashion changed, the supply of beaver depleted, the mountain men turned their talents and knowledge of the vast area to other pursuits.

“The mountain men were but the prelude to the large intrusion of Americans. The trappers showed the way to the traders who were soon to follow in large numbers.

“It was not until 1821 when Mexico attained its independence from Spain, that the American traders were successful.

“In 1819 an appeal was made to the government for a military escort for the Santa Fé caravan. Washington officials did not understand the terrain of the land and ordered Major Bennett Riley and four companies of the sixth

infantry to accompany the caravan. Riley was successful in protecting the traders until they had passed into Mexican territory. Unfortunately, he and his group had to await the return of the caravan, and while they waited the Indians constantly harassed them. Being on foot, the soldiers were unable to protect themselves. The report of their discomfort and danger finally convinced the skeptics that a mounted force was absolutely necessary in dealing with the Plains Indians, who used the horse effectively. Thus was begun the United States Calvary.”

“Booh-YA!“ whooped Brent during the applause, “Now my bugle will be appreciated.”

“Santa Fé became the port of entry for the trade of much of the Mexican territory, with large caravans being

assembled there before making their way southward to Chihuahua or westward to California.

“ Unfortunately the Santa Fé trade brought friction between the Americans and the New Mexicans. Much of this ill feeling came from the traditional Spanish fear of interlopers, foreigners, and Protestants.

“Most Americans were Protestants. With intolerance toward the Roman Catholic faith, they seldom missed an opportunity to display it. On the other hand, the resentment against the traders was sometimes not their own fault. For example, the fear caused by the ill-fated Santa Fé Expedition in 1841 and the subsequent Texas reprisals caused all Anglos to be suspected of conniving to seize the province. After what had happened with the succession of Texas, Mexican authorities perhaps had good cause to fear the number of Americans who were moving in to New Mexico. The attempts to cut off the Santa Fé trade grew out of this fear. But New Mexico needed American goods too badly for such embargoes ever to be effective

“The Mexican War caused an almost complete collapse of normal trade on the Santa Fé road. But the needs of the military led to continuation of the caravans. Once the war was over the old trade was renewed along with regular passenger service utilizing stagecoaches.

“By 1860 nearly seventeen million pounds of freight had gone over the old trail. The business employed approximately 10,900 men needed six thousand one hundred mules, twenty-eight thousand oxen and three thousand wagons to service it. After the Civil War was over the trade continued to flourish and in some years four or five million dollars worth of goods were went out from Missouri. Such goods continued to be largely manufactured items for consumer purposes, for which New Mexico exchanged hides, skins and wool. Gold and silver were also shipped from time to time but the balance of trade remained against New Mexico. Fortunately just as in Spanish times, this deficiency was made up largely through the money brought into the territory by the army.”

The sun was just beginning to set in Mesilla that March fifth evening in 1853, when Brent and Lynae spotted Mom returning from the car with the camera. "Did I miss anything I should have gotten a picture of?" she asked cheerily. Brent and Lynae glanced around as they realized all the ancestors had disappeared and the parking lot was filled with modern cars.

"No, nothing we can't pick up on a post card of at Kit Carson's store," Brent chuckled. "While I'm there, I'm going to smash me some souvenir penny's in the machine for my collection.”

"Oh, while I was digging in the camera bag, I found this story Uncle Eliseo sent for genealogy. I brought it along so we could read it while we eat our lunch on that grassy slope there."

Mom missed the look that passed between Brent and Lynae as they headed for the picnic spot on the hill.

“I didn’t realize New Mexico was so involved in the Civil War! Look at this article I found on the Internet.

[2] There were at least two battles fought right in New Mexico when the confederates attempted to take it over! Here’s a long list of soldiers that fought on both sides. One battle was lead by two commanding officers, brothers-in-law, who fought on opposite sides. The author even included actual letters in a newspaper from survivors who remember it from each side.”

“Where would our family fit in with the Civil War?” Brent asked, as he carefully returned the Beaver hat to the store counter.

“Well, the Civil War. That would be about the time of my great grand father, José María Baca. The Civil War came less than a generation after the conquest by general Kearney and the Mexican War. It was during the war with Mexico that the Mormon Battalion was called upon to leave their families crossing the planes from Nauvoo to Utah, and march to battle for the Union which had just persecuted them, chasing them from Missouri with threats of extermination. Brigham Young promised the men if they would be faithful they would not have to enter into a battle and all would reunite with their families. So to prove their loyalty to the United States, and to earn extra money for their families to make the journey west, they marched in a unit called Mormon Battalion.

The issues of slave holding, commercial interests, and even political interests in having New Mexico secede from the union all played a part. Breaking up the United States may have seemed like a new chance for independence for the generations of New Mexicans who had been raised during the wild rebellion around 1847, and the Gold Rush at the end of that decade. This was the era of stagecoach mail, which shaved the trip from Santa Fé to Kansas City to under eleven days. The economic growth of those two decades was impressive as more and more Americans flowed into the west and through New Mexico. Even after the Civil War slave holding continued in New Mexico as in other states, illegally.

José María

In 1862 a Confederate Army troop headed by H. H. Sibley led an attack against a Union army and captured Albuquerque and Santa Fe. Then Governor Gilpin of Colorado organized an infantry and cavalry to cross through the Raton Mountains in February, marched sixty seven miles in a single day to arrive at Fort Union, then set out to recapture Santa Fe. They had to fight more confederate troops in Apache canyon, then march on to more battles until the confederates were defeated and retired with no supplies first to Santa Fé then to valley of the Río Grande. Colonel Kit Carson was involved in this battle which was the last in which Confederates were a serious threat in New Mexico. They withdrew completely by August. Confederate raiders continued to attack various places along the Santa Fé trail until the close of the war in l886.

[3] Let’s read what Uncle Eliseo had to say about that time period in our family.

[1] Author of 50 Nifty states -- -

[2] Http://www.nmgs.org/artcw.htm

[3] Coronado pp 245-47